Bertrand Lavier

The relationship between reality and the tools of its representation, from verbal communication to the visual arts, guides the artistic investigations of Bertrand Lavier. Carrying out an analysis not unlike Michel Foucault’s studies on language, Lavier uses his work to expound upon the continuous detachment of things from the words that attempt to define them. Through his works, the artist establishes a process of destabilization, which tends to demonstrate, as he observes, “that it is language that determines reality and not vice versa.” Rather than positioning themselves as reassuring bestowers of unambiguous meaning, his works often function as logical traps.

Calling into question the criteria that separate the artistic sphere from everyday life, Lavier impartially adopts materials belonging to both realms. In the early 1980s he began covering common objects with acrylic paint, using the same colors characteristic of the real object. The result is a sort of osmosis between the fluid painting and the solid to which the paint is applied, which produces works capable of destabilizing the boundaries between the category of painting and that of the object.

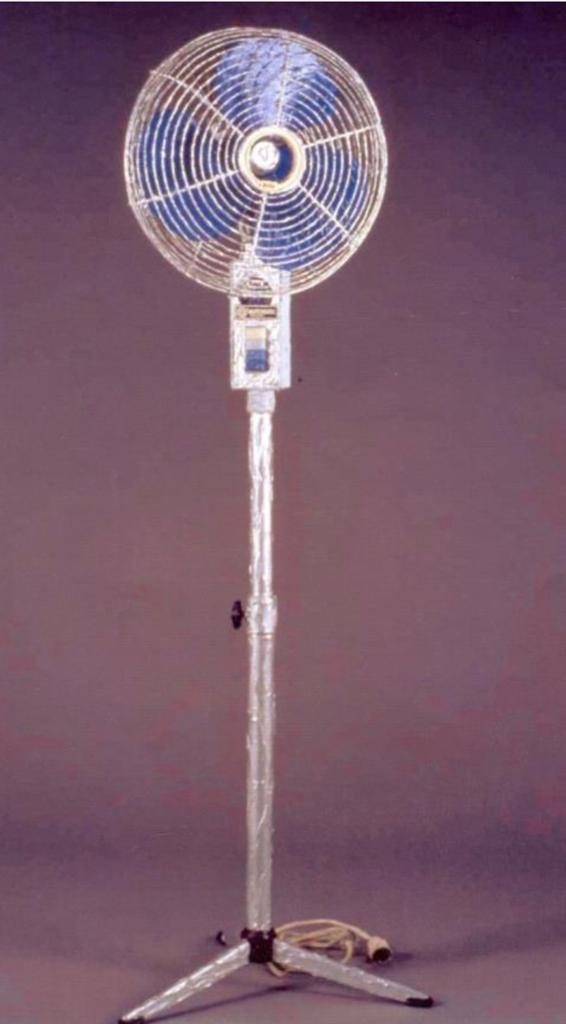

In Steinway and Sons, 1987, the artist uses an actual grand piano produced by the famous American company. Deprived of its functionality, the piano is covered by broad brushstrokes of acrylic color, reproducing the ideal pictorial touch that defines the modern artistic canon, from van Gogh to Neo-Expressionism. At the same time the tautology inherent in Lavier’s operation, in which painting is pure coating that replicates what it is covering, drains the pictorial gesture of any theatricality. A similar principle is at stake in Ventomatic, 1982, where a fan is covered with brushstrokes of acrylic paint that reiterate the color and details of the object. Even in this case, the object has a sound functionality that the artistic operation intentionally denies.

Expanding his investigation to spaces that are intended to accommodate art, Lavier extends his action to architectural details of museum galleries, as in the case of Fenêtre (Window), 1982–96, created by the artist on a window of the Castello, in conjunction with his solo exhibition. In keeping with the artist’s technique, each detail of the object is painted the same color as the object itself, including the glass panes, which are covered with transparent acrylic paint.

A different reversal of artistic conventions occurs in Mobymatic, 1993. Without any formal intervention on the part of the artist, the work presents a damaged moped as a sculptural object. In this case, as in other works created the same year, Lavier re-proposes the idea of the ready-made—the object taken from life and presented in an artistic context, as undertaken first by Marcel Duchamp—calling it a “ready-destroy.” Unlike Duchamp, he focuses on objects that connote possibly tragic implications. The flashily damaged moped refers to a dramatic story, one able to stir up emotions. The title of the work, however, does not legitimize a precise narrative and simply repeats the brand name of the object.

Guzzini, 1996, also has a brand name as its title. The piece consists of lamps mounted onto their fixtures. In this case the material employed refers to the gallery or museum context, transforming into a work of art some of the technical equipment that usually surrounds the work, and exhibiting an empty space in which the light emitted by the lamps illuminates nothing.

[MB]