Maurizio Cattelan

The works of Maurizio Cattelan seem to impose themselves forcefully on reality and, acting as disturbing elements, disrupt the world’s established order. As the artist has stated, his methodology is based on the idea of “borrowing.” Images and situations that belong to society are reworked and become existential reflections or commentaries on social and cultural dynamics that relate to the context in which the piece is presented. Each of Cattelan’s works is open to numerous interpretations, sometimes of a contradictory nature. Instead of offering certainties, the work extends doubts, mirroring contemporary consciousness.

The artist’s work often has an element of parody. For Il Bel Paese (The Beautiful Country), 1994, he enlarged the label of the eponymous cheese to make a circular rug. The flattering metaphor of the title, used by Dante and Petrarch to refer to the marvels of the Italian peninsula, is thus corrupted and transformed into an element that can be trampled and potentially ruined by the continuous passage of visitors.

The title of Charlie don’t surf, 1997, comes from the film Apocalypse Now by Francis Ford Coppola, related to a scene in which American soldiers fighting in the Vietnam War attack and destroy a village in order to reach a beach and surf the waves. Developing a further reflection on the infinite variations of human cruelty, the work takes the form of a mannequin with the features of a young boy, seated at his school desk. Apparently diligent, the pupil is constrained into a situation of forced immobility. A closer look reveals that, pierced by pencils, his hands are nailed to the desk.

A different allusion to an existential condition, where the subject is deprived of any possibility of action, is elaborated in Novecento (1900), 1997. The work consists of an embalmed horse hung from the ceiling by a sling. The animal’s neck is bent downward and the hooves, stretched out during taxidermy, extend toward the ground. A new take on the concept of natura morta (“still life,” literally “dead nature”), the final image is one of frustrated tension, of energy destined to find no outlet. By the artist’s own admission, insecurity is a defining aspect of his approach, and the idea of failure is a theme that recurs in many of his works.

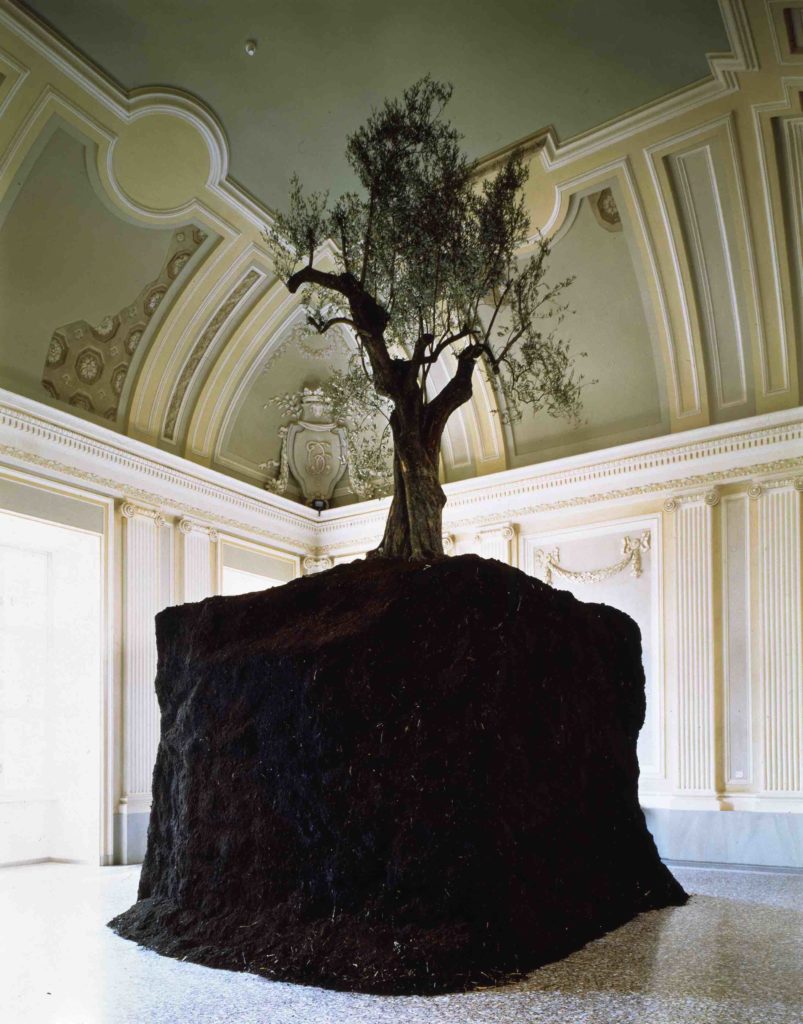

An ambiguity of message is always present in Cattelan’s work. A live olive tree and a large mound of earth containing the tree’s roots make up the installation Senza titolo (Untitled), 1998. Traditionally associated with the divine, the olive tree in Christian symbolism stands for the restored alliance between God and men. In a more strictly artistic context, the tree brings to mind Arte Povera’s characteristic focus on natural materials and primal energies. However, nothing in Cattelan’s installation can really be connected to the multiple symbologies linked to the figure of the tree. Rather, the imposing scale of the installation and the large patch of earth surmounted by the olive tree that looms over the viewers seem like an abnormal “slice of life” forcibly brought into the museum.

During the course of his career, Cattelan has created performances in which he asks his art dealers to exhibit themselves, disguised in specially designed costumes. In the case of his Milan dealer, the artist decided to literally attach the dealer to the wall, just as he was, with strong adhesive tape. The harsh treatment, almost like a crucifixion, can be interpreted as a commentary on the up-and-down power relationship that exists between artists and their dealers. The photograph Senza titolo (Untitled), 1999, was taken on the occasion of this performance, which was held for a few hours at Massimo De Carlo Gallery in Milan.

[MB]