Calligrammes – Lythos de Chirico

Artists Guillaume Apollinaire, Giorgio de Chirico

Calligrammes – Lythos de Chirico

Librairie Gallimard, Paris 1930

no. 88 of 88 copies on China paper numbered from 13 to 100, loose-leaf folios 33 x 25.1 cm

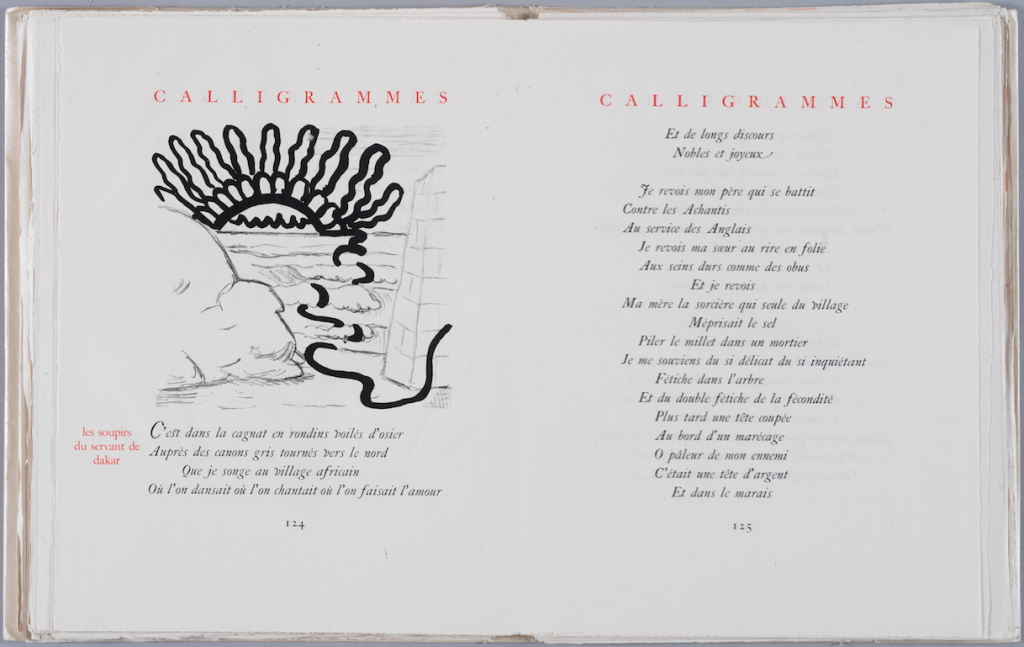

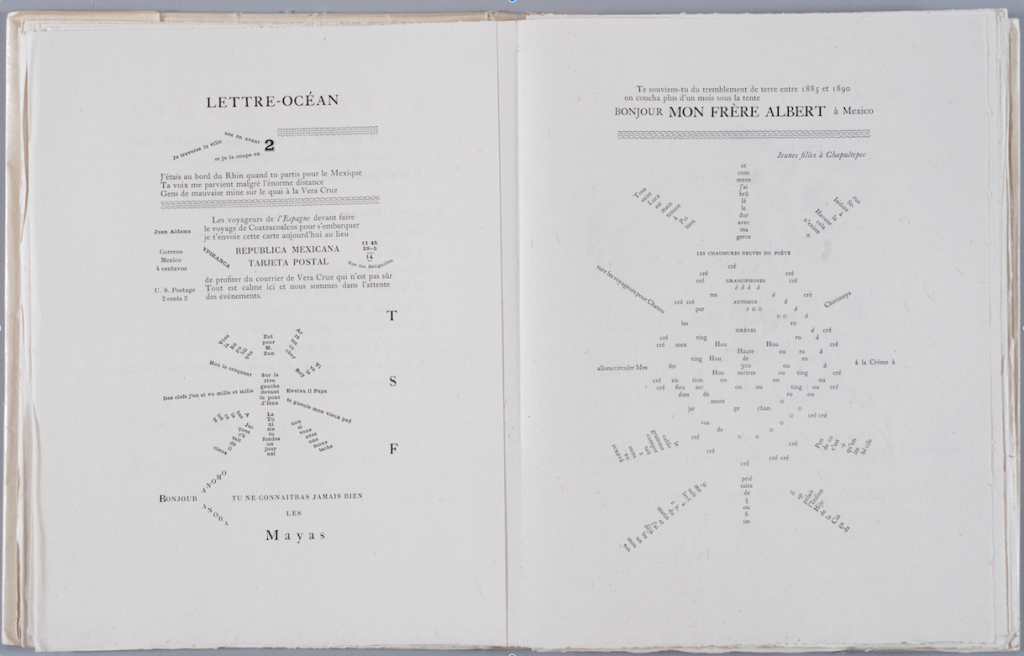

Original soft cover with lithograph on the front board. Original chemise and hardbound case with decoration in black and red on white. 269-(7) numbered pages. Text printed in red and black with 66 original lithographs designed on stone by Giorgio de Chirico and printed by Edmond Desjobert, 2 of which repeated on the cover and frontispiece. Signed bottom right on the colophon: “G. de Chirico”.

Collection Fondazione Francesco Federico Cerruti per l’Arte

Long-term loan Castello di Rivoli Museo d’Arte Contemporanea, Rivoli-Turin

Inv. no. CC.20.L.1930.E41

Exhibitions: M. T. Roberto with V. Bertone, F. Bruera, M. Pronesti (curators), Apollinaire e l’invenzione “surréaliste”. Il poeta e i suoi amici nella Parigi delle avanguardie, exhibition without catalogue (Turin, Galleria d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea, 31 October 2018 – 24 February 2019).

Bibliography: Vitali 1931, pp. 75, 88; Ciranna 1969, pp. 7-8, 37-104, nos. 17-82; Hyde Greet 1977; London 1985; New York 1992-93, p. 163, no. 163; Christov-Bakargiev 2021, vol. I, p. 316.

“It will certainly not be long before it becomes a brave phalanx [of artists] that will make the illustrated book of the 20th century famous.”1 Thus it was in 1914 that Guillaume Apollinaire announced the birth of 20th-century art books, a precious example of which is provided by his own Calligrammes with lithographs by Giorgio de Chirico, published by Gallimard in 1930. Early that year, Apollinaire began to develop a new relationship between word and image by arranging verses on the page so as to form a drawing. He intended to present his first pictorial poems in an “album of lyrical, coloured ideograms” entitled Moi aussi je suis peintre,2 which de Chirico referred to in a letter: “In return for the paintings I have given you […], I will ask you to dedicate to me one of the poems that are about to be published in a book, as you told me yesterday.”3

The printing of this book was prevented by the outbreak of World War I and the collection of Apollinaire’s poems subsequent to 1913 was published in 1918 by Mercure de France with a title that established the definitive name of his pictorial poems and a subtitle referring specifically to the historical context: Calligrammes. Poèmes de la paix et de la guerre.4 De Chirico’s request was granted. He was the dedicatee of “Océan de terre”, written in 1915 at the front, when the horizon seen from the trenches was a dark ocean of earth.5

In Ferrara, a few days after Apollinaire’s death in November 1918, the painter recalled their relationship four years earlier in Paris – “I remember his numismatic profile, which I printed on the Veronese sky of one of my Metaphysical paintings”6 – and described calligrams as “poems in which the verses gently wander […], tracing the rectangles and spirals of his chronic melancholy over the white of the paper”.7 De Chirico moved back to Paris in 1925. A commission to illustrate Calligrammes enabled him to assert his past friendship with Apollinaire, who invented the term surréaliste in 1917, at a time when his recent paintings had given rise to a bitter clash between the Surrealists, who saw their archaeological themes as a betrayal of Metaphysical art, and those who defended them, like Waldemar- George and Jean Cocteau. Waldemar-George’s monograph, Cocteau’s Mystère laïque and André Breton’s Le surréalisme et la peinture were all published in 1928 and illustrated with reproductions of works by de Chirico, who made the relationship between literature and image a central theme of his novel Hebdòmeros. Le peintre et son génie chez l’écrivain the following year.

The typesetting of the Gallimard limited edition of Calligrammes, of which the Cerruti Collection holds one of the copies on China paper, was the work of the printer Maurice Darantière, who used the Garamond typeface with square capitals and italics in black and red ink. De Chirico was asked to undertake a paradoxical challenge with a technique practically unknown to him at the time, namely lithography. While the relationship between text and image is developed typographically in Apollinaire’s calligrams, the artist’s lithographs shifted this balance in another direction through the dreamlike timbre of iconographic invention and sinuousness of the line, “where absolute blacks stand out against silvery greys”, as Lamberto Vitali noted as early as 1931.8

It was also in 1931 that de Chirico told the collector René Gaffé that he had drawn inspiration for his illustrations from the verses in which Apollinaire speaks of suns and stars – read in Paris in 1914 thinking about Italy and its cities and ruins, and about suns and stars that return to earth like emigrants, extinguished in the sky but rekindled in the windows and doorways of houses.9 One of the verses that forms the image of a house in the calligram “Paysage” is indeed “voici la maison où naissent les étoiles et les divinités”.10 One of the poems by Apollinaire read by de Chirico in 1914 in the pages of Les Soirées de Paris thus provided the stimulus for the image of the fallen sun, recurrent in the lithographs for Calligrammes and then a frequent presence in his subsequent work.

[Maria Teresa Roberto]

1 “Nul doute qu’avant qu’il ne soit longtemps elle ne devienne une vaillante phalange [d’artistes] qui rendra illustre le livre illustré du XX° siècle.” G. Apollinaire, “Livres d’art”, in Paris-Journal, 26 July 1914; now in Apollinaire 1960, p. 519.

2 This is how the work was described in the advertisement for subscriptions that appeared in 1914 in Les Soirées de Paris. For his project and Apollinaire’s earliest ideograms, see C. Debon, “Et moi aussi je suis peintre?”, in Paris 2016, pp. 230-243.

3 “En échange des tableaux que je vous ai donnés […], je vous demandarai de me dédier une des poésies que, comme vous me dites hier, vous allez publier prochainement en volume.” Letter from de Chirico to Apollinaire, undated but written at the end of January 1914, in Apollinaire 2009, pp. 786-787.

4 Calligrams alternate in this publication with traditionally printed poems and reproductions of handwritten pages from the months serving at the front.

5 “Océan de terre”, the last poem in the “Lueurs des tirs” section of Calligrammes, was first published in the magazine Nord-Sud in February 1918 with the date December 1915 and a dedication to de Chirico.

6 De Chirico 1918, p. 7. For the 1914 portrait of Apollinaire mentioned here, now in the Musée National d’Art Moderne in Paris, see Fagiolo dell’Arco 1981b.

7 De Chirico 1918, p. 8.

8 Vitali 1931, p. 88.

9 For René Gaffé’s conversations and contacts with de Chirico, see Gaffé 1946.

10 The third in the “Ondes” section of Calligrammes, this poem was first published with the title “Paysage animé” in the July-August 1914 issue of Les Soirées de Paris.